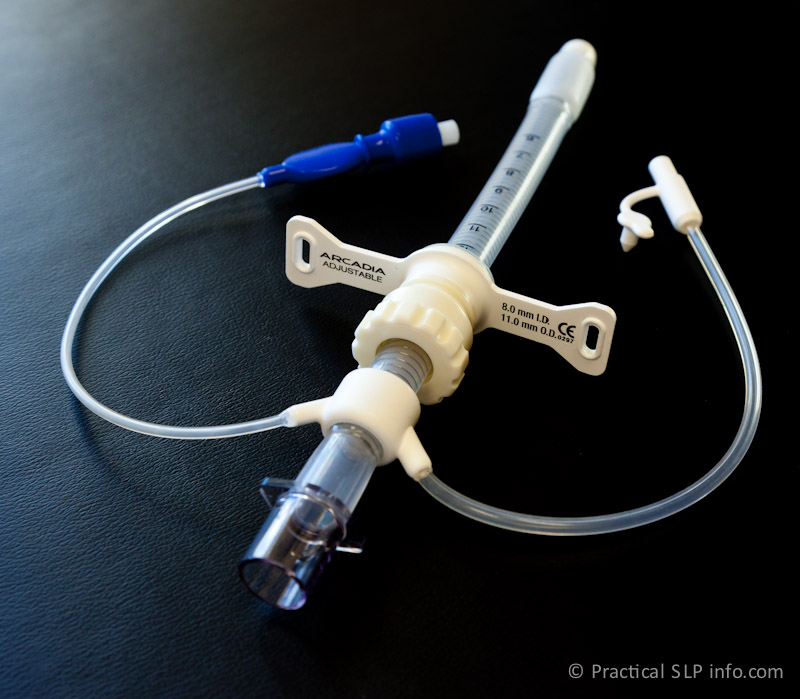

High Volume - Low pressure

This is the most common cuff found on a standard tracheostomy tube. These cuffs have a larger structure and, in turn, surface area against the trachea, using a higher volume of air to inflate the “balloon.” In this sense, the contact area against the trachea is larger, allowing the potential for a better seal. Similarly, because of the high volume of the balloon and greater surface contact against the trachea, an effective seal can be established without a great deal of pressure against the trachea.

The drawback to this form of cuff also pertains to the larger size of the “balloon.” Even when entirely deflated, the shell of the cuff fills the trachea to some extent. Consider a grape vs a raisin. An inflated cuff is like the grape. The air in a cuff is like the water in a grape. Although a raisin is smaller than the grape, it still has a volume. The same is true of the cuff. It may “shrivel” once the air if removed, but it still occupies space in the trachea, more than just the tube shaft itself.

When weaning from a tracheostomy tube or when using a speaking valve, the extra volume of a deflated high volume/low pressure cuff may have a negative impact on the expected outcomes.

Low VOlume - High Pressure

In general, these cuffs are not ideal for patients requiring long-term use of a cuff. These cuffs typically conform to the shaft of the tube, expanding when air is inflated under high pressure.

The benefit of these cuffs is that the tube can act essentially as a cuffless tube, although has the potential for cuff inflation when needed. However, since these are high pressure inflations, the surface pressure against the tracheal wall is also quite high and may present a risk for tissue damage if used over a prolonged period of time.

So why these cuffs? Unlike the high volume/low pressure cuff, there is no residual space taken up in the trachea when this cuff is deflated. In most cases, with full deflation, this cuff will adhere to the shaft of the tube.

In some cases, then, this type of cuff can be ideal. For example, consider a tracheostomy patient. not ordinarily needing cuff inflation, however, may need to undergo one or more future procedures under anesthesia. Since a cuff is required to maintain adequate ventilation while under anesthesia, this presents and ideal situation. The patient can experience the benefits of a cuffless trach, although no tube change will be required for general anesthesia as the cuff can be inflated for the procedure (short-term), and then deflated for normal breathing/speaking.

Foam Cuff

This is the least commonly used cuff although is found to be helpful in some cases. The foam cuff is exactly that: instead of air-filled, it is foam filled and this offers certain benefits.

Consider the properties of foam in general:

Even when air, water, etc, is squeezed from foam, when left untouched, it spontaneously fills with air. In fact, it fills with air. Based on certain laws of physics, it will spontaneously inflate to atmospheric pressure. The is the pressure in which we all live our lives! It is the pressure of our surrounding atmosphere and what our tissues are designed to withstand.

So! It is clear then, that a cuff inflating to atmospheric pressure would be the best possible scenario for allowing the trachea to be adequately sealed, while also no exerting too much pressure against the tube! Right? So why not use a foam cuff for everyone?

Consider how the high volume cuff still occupies some of the space in the trachea even after full deflation. Now consider how much space foam would occupy, even fully deflated. That factor, along with the risk of spontaneous inflation (NOT ok when a speaking valve is in place), as well as routine maintenance this cuff requires, makes this cuff less than ideal for many patients.

There are, however, patients that benefit greatly from this cuff. For example, f long-term cuff inflation is required (i.e., prolonged dependence on mechanical ventilation), AND the patient has experienced tracheal damage from excessively high cuff pressures, this may be an ideal solution.

Consider the properties of foam in general:

Even when air, water, etc, is squeezed from foam, when left untouched, it spontaneously fills with air. In fact, it fills with air. Based on certain laws of physics, it will spontaneously inflate to atmospheric pressure. The is the pressure in which we all live our lives! It is the pressure of our surrounding atmosphere and what our tissues are designed to withstand.

So! It is clear then, that a cuff inflating to atmospheric pressure would be the best possible scenario for allowing the trachea to be adequately sealed, while also no exerting too much pressure against the tube! Right? So why not use a foam cuff for everyone?

Consider how the high volume cuff still occupies some of the space in the trachea even after full deflation. Now consider how much space foam would occupy, even fully deflated. That factor, along with the risk of spontaneous inflation (NOT ok when a speaking valve is in place), as well as routine maintenance this cuff requires, makes this cuff less than ideal for many patients.

There are, however, patients that benefit greatly from this cuff. For example, f long-term cuff inflation is required (i.e., prolonged dependence on mechanical ventilation), AND the patient has experienced tracheal damage from excessively high cuff pressures, this may be an ideal solution.

Your doctor will always determine the most appropriate tube for you, based upon your unique medical needs. Should you have any questions regarding your tube, your doctor or SLP staff will be happy to address these further.